A Christian reader asked a good question.

"Who did Paul address his letters to the Galatians , Corinthians and Thessalonians to, except the Churches in those areas? Also Romans 16:16 all the churches of Christ greet you, Paul's journeys recorder in the book of acts were for the very purpose of Setting up individual autonomous churches in each area he traveled to."

My response is as follows:

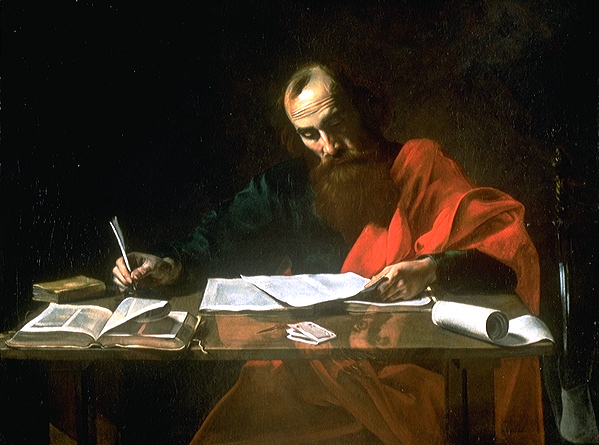

Paul refers to the 'church ' as the "body of Christ." The clusters of early Christians that Paul is writing to are not organized institutions as we commonly think of when thinking about modern churches. Paul, as he himself states numerous times in his letters, is working diligently to unify the "body of Christ," that is the early Christian communities he is in contact with, and get them spiritually ready for the Second Coming.

It seems to me a historiographical mistake to confuse our modern concept of the church with what Paul actually meant.

My Christian friend responded:

"For the most part I agree the New Testament church is nothing like the churches we see today, but it is a local congregation or assembly of Christians in a given area, and it had certain rules and regulations to adhere to. It is nothing like today's churches in that it was always only a local congregation ruling itself from the bible, there is no head office no meeting of the elders of several churches to see whats the best plan for the church it was always meant to be just an autonomous assembly of christians serving the lord in a given area, but it was still planned, organised and defined by rules so from that stand point it was an institution."

It seems to me, from what I have read, that there wasn't any such semblance of organization in the groups of Gentile Christians as spoken about in Paul's letters--at least not to the extent you seem to be thinking.

Again, just to clarify, Paul merely only meant "church" insofar as it represented "the Body of Christ." The terms "church" and "the Body of Christ" are used synonymously throughout the NT for the early Christian community (i.e., those who have come accept Christ as the redeemer).

Perhaps I should explain further why I do not believe there was any evidence of organization, with no actualized rules, and with little in the way of agreed thought or opinion within the early Christian community.

It is well known in the ancient letters outside of the Bible that even 200 years after Christ that most people were still in the dark as to what constituted a Christian or what it is that Christians even believed. For example, in the scrolls of Octavius, written by the third-century author Minucius Felix, there are comments of locals recorded in which people are baffled as to what the practices and rights of Christians really were.

Ancient people were weary of Christians because they frequently met after dark or before dawn, and their meetings changed from home to home each week, and these *secret meetings were exclusive to *only Christians. There were rumors that "Christian love" was a metaphor for incest and sex orgies supposedly held after dark during these highly secretive meetings. One of the popular rumors in the ancient times was that Christians ate babies and drank their infant blood!

People didn't say all this because they hated Christians. They said this because early Christians were so secretive--to the point of being exclusionary. Whereas Pagan religions intermingled, Christians kept to themselves, yet shunned all other religions as false. Most early Christians didn't invite trust or encourage understanding in others. People reacted out of *fear toward Christians--the fear of not knowing.

Christian persecution under Nero was probably largely related to the same effect, since Christians refused to partake in the national religious observances, and kept to themselves, and seemingly worshiped a political radical who was criminally condemned and sentenced to death, Nero was worried that there might be an uprising and rebellion, as Tacitus wrote, and so persecuted Christians as a means to weed out their supposed plot to overthrow the empire. It is even rumored that Nero himself may have started the fires which decimated large parts of Rome in 64 A.D. as a means to drive out the Christian populace for strategic reasons, at least according to Suetonius.

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, writing in 180 A.D., went through great pains to alleviate the unjust attacks on Christians--yet he too admitted in his Meditations that he didn't know what Christians actually believed.

My point here is that although it seems there is a minuscule amount of organization within the small assemblies of Christians gathering in the second to fourth centuries--we are still completely in the dark as to their official beliefs and practices as a community--except for the nasty rumor mill which showed a weariness toward Christian custom and behavior which was both highly exclusivist and secretive.

Suffice to say, this lack of understanding of ancients with regard to Christianity compounds our contemporary lack of understanding for the same time periods. It is all shrouded in mystery, especially since nobody then knew what Christians might have believed--or how they organized themselves--or by what religious observances they gathered in secret to practice--we simply cannot assume they were well organized or structured.

At best these assemblies, and I use the term loosely, resembled rural peoples gathering for festivities more than actual planned religious meetings. As Christian orthodoxy has always been an ongoing enterprise, it seems that institutional thought couldn't have fully developed before Paul actually had written much of it down, and then it would still be hundreds of years more until orthodox thought and opinion finally congealed, long after the early church fathers and theologians had set down doctrines, regulations, agreed upon creeds, and began to build a hierarchy of institutional observances to better define the Christian faith by. Only after all this was there something for Christians to unite around. Before these events, however, Christianity is a vague hodgepodge of thoughts and opinions--almost none of them agreeing.

Now let's go back earlier, to the first century, when Paul lived and wrote.

What stands out to me, especially in Paul's letters to the "churches," was that he was addressing the social problems of individuals. In one Christian community (which is all Paul's term of "church" signifies) a guy is accused of incest, of sleeping with his step-mother, while in another an unspecified person is still practicing pagan rights alongside their newly established Christian ones. Within the all of the "churches" there is insensible bickering of what Christian beliefs, practices, and spiritual rights should be, which ones are to be deemed correct and which are not, and the only thing which is clear (at least to me) is that nobody (and I mean nobody at all!) had a firm idea of what Christianity meant.

Except for, perhaps, Paul--who was always certain. He was on a mission to right every wrong. Which is why he wrote these letters to his "churches." He wanted them to conform to his standard of Christian values, practices, and beliefs.

Early Christianity is an enigma. Nobody really knows how it formed with any certainty. All we can do is create historical reconstructions which best account for all the available data. Even so, it is important that we remember Paul's version of Christianity is just the one that ultimately won out. But in his day, there were numerous strands of Christian thought all volleying for the dominant position. There was the Peter/James group, there were Gnostics, there were Simonians, there were Docetists, and many more varieties of Christianity just in Paul's day alone!

So all we really know about the early "church" was that there wasn't one.

Christians met in secretive locations--a practice which lasted up to three hundred years, they frequently changed locations, they had no leadership--which is why Paul kept writing to them demanding that they get their houses in order--so to speak, they had no unity of thought, they bickered constantly, and so on and so forth. I find it hard to see how any of this signifies an institution of cohesion of thought and opinion. Indeed, I don't believe we see strands of orthodoxy emerge until the mid to late second century--so there would be nothing for the early Christians to unify around--therefore there truly could be no Christian institutions until much later.

Meanwhile, Paul tried to wrangle in the groups he was primarily responsible for creating in the first place--his gentile Christian mission--and his letters show his struggle to unify them and prepare them spiritually for the end times. But I see no semblance of institutional thought--at least not until a time when there is a more rigid form of orthodoxy to adhere to, which begins to emerge primarily in the latter half of the second century.

It is well known in the ancient letters outside of the Bible that even 200 years after Christ that most people were still in the dark as to what constituted a Christian or what it is that Christians even believed. For example, in the scrolls of Octavius, written by the third-century author Minucius Felix, there are comments of locals recorded in which people are baffled as to what the practices and rights of Christians really were.

Ancient people were weary of Christians because they frequently met after dark or before dawn, and their meetings changed from home to home each week, and these *secret meetings were exclusive to *only Christians. There were rumors that "Christian love" was a metaphor for incest and sex orgies supposedly held after dark during these highly secretive meetings. One of the popular rumors in the ancient times was that Christians ate babies and drank their infant blood!

People didn't say all this because they hated Christians. They said this because early Christians were so secretive--to the point of being exclusionary. Whereas Pagan religions intermingled, Christians kept to themselves, yet shunned all other religions as false. Most early Christians didn't invite trust or encourage understanding in others. People reacted out of *fear toward Christians--the fear of not knowing.

Christian persecution under Nero was probably largely related to the same effect, since Christians refused to partake in the national religious observances, and kept to themselves, and seemingly worshiped a political radical who was criminally condemned and sentenced to death, Nero was worried that there might be an uprising and rebellion, as Tacitus wrote, and so persecuted Christians as a means to weed out their supposed plot to overthrow the empire. It is even rumored that Nero himself may have started the fires which decimated large parts of Rome in 64 A.D. as a means to drive out the Christian populace for strategic reasons, at least according to Suetonius.

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, writing in 180 A.D., went through great pains to alleviate the unjust attacks on Christians--yet he too admitted in his Meditations that he didn't know what Christians actually believed.

My point here is that although it seems there is a minuscule amount of organization within the small assemblies of Christians gathering in the second to fourth centuries--we are still completely in the dark as to their official beliefs and practices as a community--except for the nasty rumor mill which showed a weariness toward Christian custom and behavior which was both highly exclusivist and secretive.

Suffice to say, this lack of understanding of ancients with regard to Christianity compounds our contemporary lack of understanding for the same time periods. It is all shrouded in mystery, especially since nobody then knew what Christians might have believed--or how they organized themselves--or by what religious observances they gathered in secret to practice--we simply cannot assume they were well organized or structured.

At best these assemblies, and I use the term loosely, resembled rural peoples gathering for festivities more than actual planned religious meetings. As Christian orthodoxy has always been an ongoing enterprise, it seems that institutional thought couldn't have fully developed before Paul actually had written much of it down, and then it would still be hundreds of years more until orthodox thought and opinion finally congealed, long after the early church fathers and theologians had set down doctrines, regulations, agreed upon creeds, and began to build a hierarchy of institutional observances to better define the Christian faith by. Only after all this was there something for Christians to unite around. Before these events, however, Christianity is a vague hodgepodge of thoughts and opinions--almost none of them agreeing.

Now let's go back earlier, to the first century, when Paul lived and wrote.

What stands out to me, especially in Paul's letters to the "churches," was that he was addressing the social problems of individuals. In one Christian community (which is all Paul's term of "church" signifies) a guy is accused of incest, of sleeping with his step-mother, while in another an unspecified person is still practicing pagan rights alongside their newly established Christian ones. Within the all of the "churches" there is insensible bickering of what Christian beliefs, practices, and spiritual rights should be, which ones are to be deemed correct and which are not, and the only thing which is clear (at least to me) is that nobody (and I mean nobody at all!) had a firm idea of what Christianity meant.

Except for, perhaps, Paul--who was always certain. He was on a mission to right every wrong. Which is why he wrote these letters to his "churches." He wanted them to conform to his standard of Christian values, practices, and beliefs.

[I should note here that most of the Christian communities Paul wrote to were unaware of anything he said in the other letters which that he sent to the other "churches." That is, the Galatians didn't know what it is Paul wrote to the Corinthians, or vice versa. In other words, one community of Christians had no way to compare their notes with another community of Christians and discover the correct teachings (according to Paul). But this just goes to show that Paul wasn't interested in establishing a core set of tenets for everyone to abide by, but that he was trying to prepare each individual community for the Second Coming, and get them spiritually conditioned for "The Day of the Lord."]

Early Christianity is an enigma. Nobody really knows how it formed with any certainty. All we can do is create historical reconstructions which best account for all the available data. Even so, it is important that we remember Paul's version of Christianity is just the one that ultimately won out. But in his day, there were numerous strands of Christian thought all volleying for the dominant position. There was the Peter/James group, there were Gnostics, there were Simonians, there were Docetists, and many more varieties of Christianity just in Paul's day alone!

So all we really know about the early "church" was that there wasn't one.

Christians met in secretive locations--a practice which lasted up to three hundred years, they frequently changed locations, they had no leadership--which is why Paul kept writing to them demanding that they get their houses in order--so to speak, they had no unity of thought, they bickered constantly, and so on and so forth. I find it hard to see how any of this signifies an institution of cohesion of thought and opinion. Indeed, I don't believe we see strands of orthodoxy emerge until the mid to late second century--so there would be nothing for the early Christians to unify around--therefore there truly could be no Christian institutions until much later.

Meanwhile, Paul tried to wrangle in the groups he was primarily responsible for creating in the first place--his gentile Christian mission--and his letters show his struggle to unify them and prepare them spiritually for the end times. But I see no semblance of institutional thought--at least not until a time when there is a more rigid form of orthodoxy to adhere to, which begins to emerge primarily in the latter half of the second century.

Without any infrastructure or organization within the early Christian community, however, it's difficult for me to see precisely what Paul's use of "church" is meant to signify--other than to say it represented the loosely assembled, yet highly disorganized, Christian communities he wrote to.

I hope that helps to answer your initial question. Thanks for the great conversation starter!

No comments:

Post a Comment